History

Raffia textiles from Congo in dialogue with the West.

The first raffia weavings from Congo were collected by Diogo Cao going up the River Congo to Sao Salvador in 1483. The cloth’s were produced by the Bakongo people. They were important diplomatic gifts and merchandise. The textiles were just as finely woven as silk and decorated with complex geometric motifs. They were sought-after objects that ended up in royal collections and kunstkammer in Europe.These are intercultural relics, products from those first contacts and exchanges..+60 examples are preserved in such European collections from the 17th century and earlier.The Pitt Rivers example was carbon dated to 1360-1438. It is assumed that this and others that appear as cushion covers could be made for the Europeans for use in a Christian context.The contact with Western traders and Christianisation influenced Bakongo art deeply.

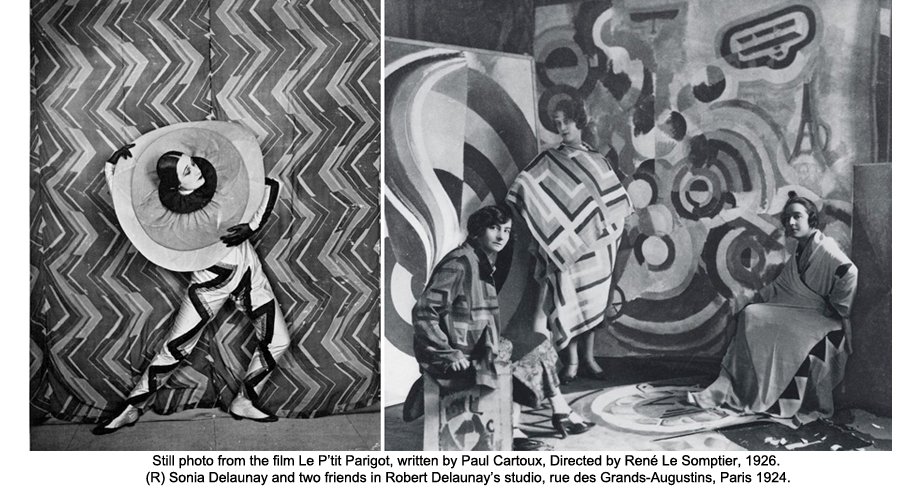

400 years later when in Europe avant-garde artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were inspired by African and Oceanic art, this determined the development of modern art. We know that masks and figures influenced expressionists, cubists, futurists, modernists, etc. Less known is the far-reaching influence of raffia weavings from Congo on these artists.

In Congo, raffia fabrics were produced by different peoples. Each had its own characteristics and techniques. The Kuba, Shoowa, Tetela, Mongo, Pende, Mbuun, Ndengese etc. each had their own tradition. When the raffia velvets from the Kuba peoples were first shown in Europe at the first colonial exhibitions, this was a true sensation.In the Salon d’honneur in the Tervuren 1897 collonial exhibition the walls of the rooms were covered with Kuba velvets in which renown Belgian Art Nouveau artists showed their ivory sculptures.(Matton,Wolfers,..)

During the colonial period in Congo Belgian Artists initiated the first generation of Congolese ‘fine’ artists’ and created the first art schools.In the early work of Djilatendo and other Congolese painters Congo textile ornaments are a returning motif.

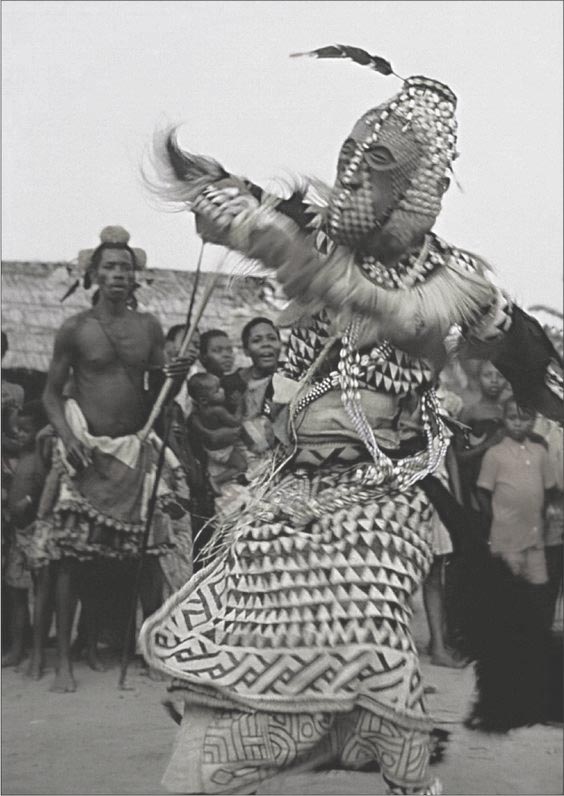

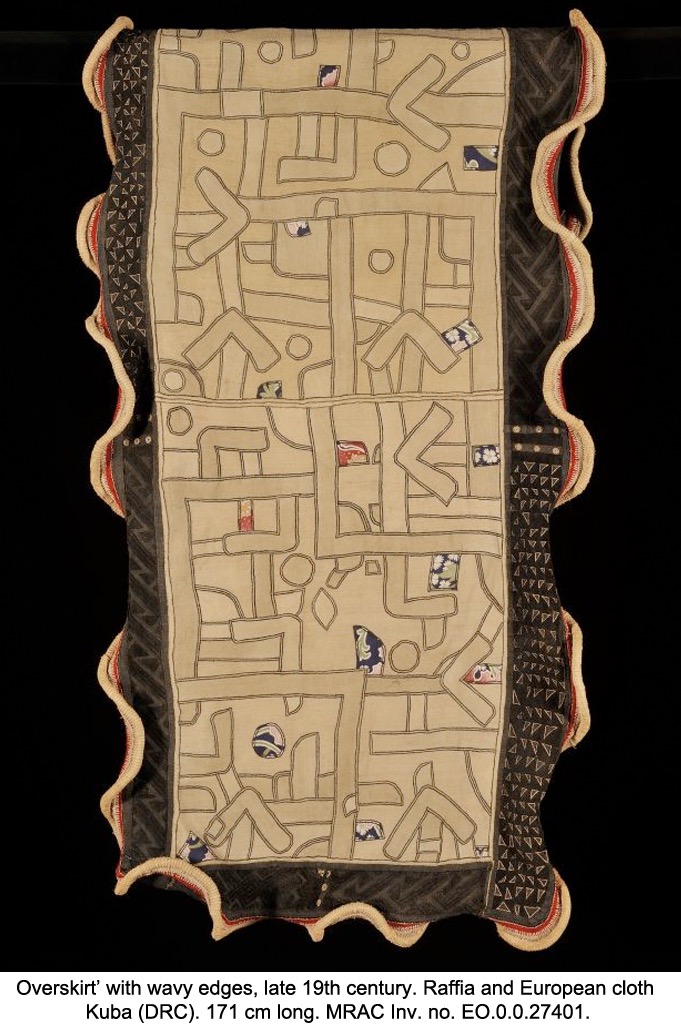

The artist women from the Shoowa peoples , a chiefdom within the Kuba empire in the interior of Kasai elevated the medium to a true art form. They use their own techniques, colors and patterns. It is part of their rich culture. The men weave the plain raffia fabrics and the women embroider and cut-pile the designs on the raffia fabric. The cloths are used as a tribute to the monarch and as a currency.The prestige cloths are accumulated by Kuba men to display their wealth. They are worn during ceremonies and funerary rites and sewn together as monumental screens for the Kuba king and his court

Their geometric compositions are unique in the world. The motifs are a language in itself that can be interpreted in different ways. Men and women read these motives differently. The central motif and background motifs are blurred in one ambiguous composition.Some motifs and patterns depict elements of the natural world other commemorate important ancestors or acclaimed women artists.Motifs used around the world like the swastika and braided knot appear in the compositions in a unique distorted way. The Kuba velours are a visual form of jazz in which motifs are repeated, varied and combined.

Kuba artisans aplied European trade cloth in their textiles in the early colonial period these were reserved for the “noble class”.

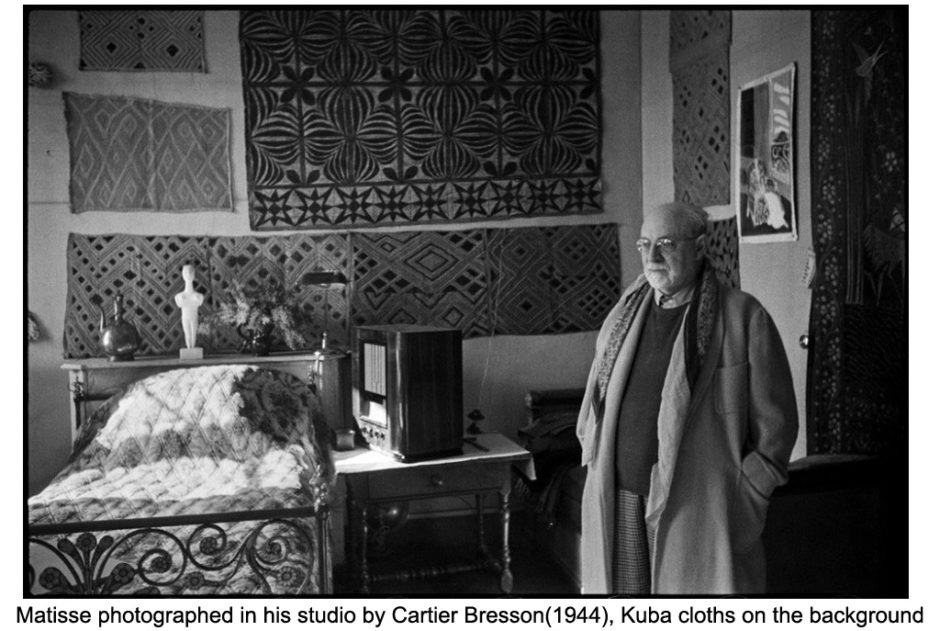

Klee, Matisse and Klimt, among others, were avid collectors of these Kuba cloths, their work was deeply influenced by them. Matisse was hit by their ‘instinctive geometry’ and Klee repainted Kuba ornamentation in his works.

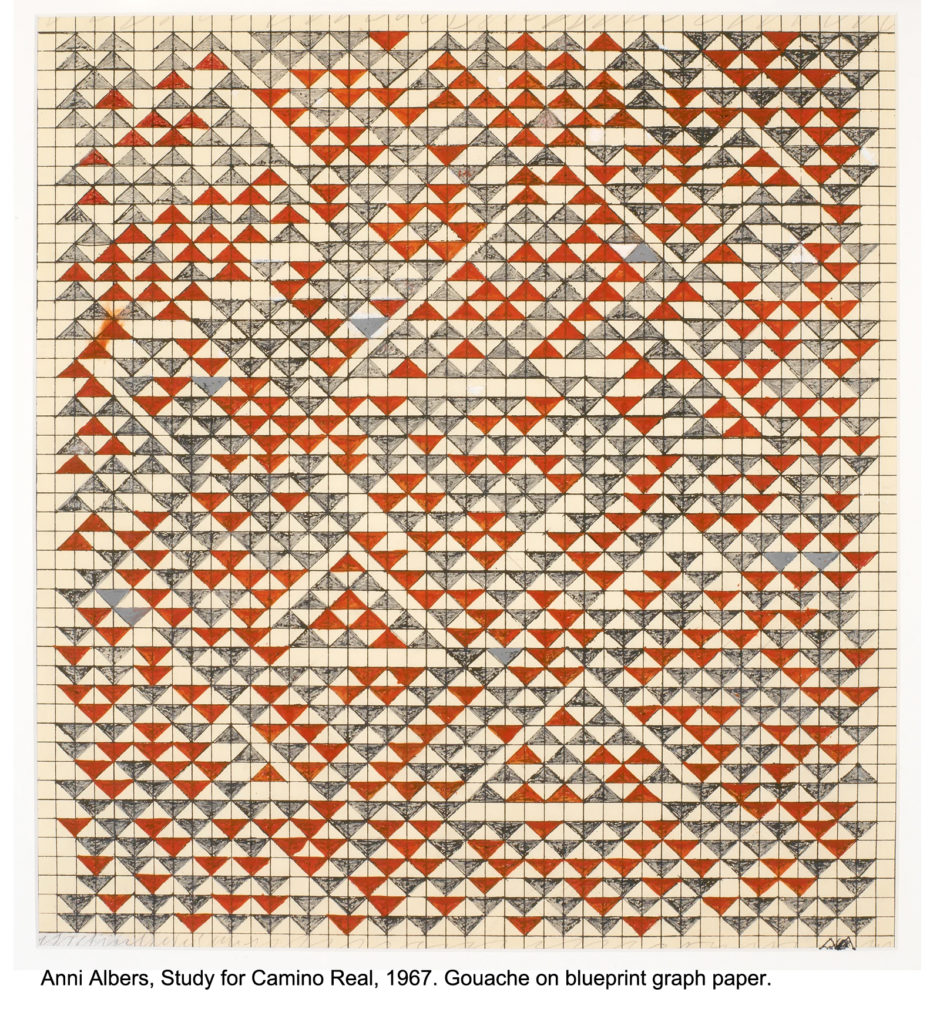

The Bauhaus had specimens in its collection. The designs of Annie and Josef Albers are a witness to this. The influence of the Kuba formal language in the West is underestimated.

Numerous examples of appropriation can be found in both the visual and applied arts. In the early colonial period, designers and architects incorporated Kuba patterns into Art Deco designs.

The missionaries in Congo, on the other hand, saw an income for their mission posts and commercialized the velours. Through the mission posts, the local arts and crafts were adapted to Christian standards and exploited. The women who made the fabrics had to follow the criteria of the mission.

Mushenge 1939,archive Kannunikesen van St. Augustinus,KADOC

-

The Order of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart arrived in the Kuba area in 1936 (Herbers 1959:53) under the guidance of Father Martin Miserez. Catholic nuns stationed at Nsheng, the Kuba capital, followed the Presbyterian lead of tapping Kuba arts as a revenuesource and between 1938 and 1951 raised money for their own school for women by exporting “Kasai velvet.” They paid a group of Bushoong women a set amount to deliver a specific number of textiles per week (Vansina 2010:275). Coming to terms with heritage Elisabeth L. Cameron

As a result, the art of Shoowa velvets changed during the 20th century. From the 1930s the velvets for local use contain more complex / busier motifs. This is explained by the social changes under the influence of the colonial regime, but it could also be an evolution in the art form.

At the same time, the compositions on the raffia velvets for export and sale became much more sterile, simpler and characterless. Because they had to be produced quickly, motifs are larger and the embroidery is less fine than before. The ambition of the nuns to ‘civilize’ the local population has an impact on the formal language. A more rigid geometric design was reserved for the ruling Bushoong class (Kuba king ) .Their velvets appear more symmetrical and regular.This style was appropriated by the missionaries as the new ideal.This devine symmetry was the new rule. Just as the Belgians tried to tame the dancing of the Congolese, the Jazz disappeared in the compositions of the Kuba velvets. These more standardised motifs were adopted after the independence and became used as symbols of the post colonial state.

Interesting to read/

Online exhibit by Celia Edwards Logan Museum https://www.loganmuseumexhibits.com/kuba-textiles

African Arts Autumn 2012 vol. 45, no. 3 Coming to Terms with Heritage. Kuba Ndop and the Art School of Nsheng. Elisabeth L. Cameron

Journal of Art Historiography Number 7 December 2012. Making and seeing: Matisse and the understanding of Kuba pattern. John Mack

Weaving Abstraction: Kuba Textiles and the Woven Art of Central Africa. – January 1, 2012 Vanessa Drake Moraga